随着人类对海洋渔业和海洋资源的持续压力,水产养殖已成为未来增加海洋鱼类产量的最有希望的途径之一。本综述介绍了水产养殖业的近期趋势和未来前景,特别关注海洋养殖和肉食性鱼类。养殖肉食性鱼类缺少益处;对鲑鱼的广泛研究表明,养殖这种鱼会对空间相距甚远的地区和各方产生负面的生态、社会和健康影响。对在海洋环境中养殖的新食肉物种的类似研究才刚刚开始,例如鳕鱼、大比目鱼和蓝鳍金枪鱼。这些鱼具有巨大的市场潜力,并可能在水产养殖业的未来方向中发挥决定性作用。我们回顾了有关肉食性有鳍鱼类水产养殖发展的现有文献,并评估了其缓解人类对海洋渔业压力的潜力。

With continued human pressure on marine fisheries and ocean resources, aquaculture hasbecome one of the most promising avenues for increasing marine fish production in the future.This review presents recent trends and future prospects for the aquaculture industry, withparticular attention paid to ocean farming and carnivorous finfish species. The benefits offarming carnivorous fish have been challenged; extensive research on salmon has shown thatfarming such fish can have negative ecological, social, and health impacts on areas and partiesvastly separated in space. Similar research is only beginning for the new carnivorous speciesfarmed or ranched in marine environments, such as cod, halibut, and bluefin tuna. These fishhave large market potential and are likely to play a defining role in the future direction of theaquaculture industry. We review the available literature on aquaculture development ofcarnivorous finfish species and assess its potential to relieve human pressure on marine fisheries.

目前研究:

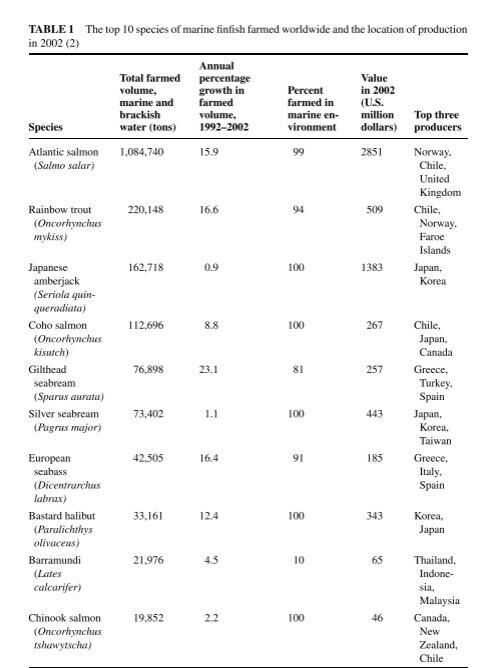

几种新的肉食性有鳍鱼类开始养殖,并可能在未来十年内改变“十大名录”(表1)的构成。对于其中一些新物种,水产养殖正在成为枯竭渔业的潜在替代品(例如,大西洋鳕鱼和大西洋比目鱼),而在其他情况下,水产养殖和捕捞产量正在同时上升(例如澳洲肺鱼和军曹鱼)与大西洋鲑鱼一样,大西洋鳕鱼在孵化场养殖并释放到海洋生态系统已有一个多世纪的历史,以增加日益减少的野生种群。然而直到1990年代,才开发出用于维持圈养亲鱼和圈养鳕鱼的技术。在现有的网栏作业中,鳕鱼通常被视为鲑鱼的可能直接替代品,因为鳕鱼生产的养成阶段几乎与鲑鱼相同。图1所示的一些主要跨国公司,尤其是Nutreco,正在引领这个行业的发展。存在一些技术障碍,例如为幼体找到合适的营养方案(与鲑鱼不同,鳕鱼幼体没有卵黄囊提供营养,需要浮游动物、盐水虾或其他活体生物作为饲料)并建立足够数量的幼体以制造可全年生产,因为鳕鱼的自然产卵周期很短。大西洋鳕鱼的商业养殖目前在挪威、英国、加拿大和冰岛建立,2002年产量约为1500吨.挪威定位于引领全球鳕鱼养殖业,就像它在鲑鱼方面所做的那样,一些消息来源预测,到2008年,挪威的产量可能达到每年30,000吨。加拿大和苏格兰紧随其后。在开发过程的这个阶段,养殖鳕鱼的商业化取决于野生鳕鱼的低捕获率和高价格以保持经济可行性。

Several new carnivorous finfish species are beginning to be farmed and are likely to changethe composition of the“top ten list”(Table 1) within the next decade. For some of these newspecies, aquaculture is emerging as a potential replacement for depleted fisheries (e.g., Atlanticcod and Atlantic halibut), and in other cases, aquaculture and capture production are risingsimultaneously (e.g., barramundi and cobia).Like Atlantic salmon, Atlantic cod have been rearedin hatcheries and released into marine ecosystems for more than a century to enhancediminishing wild populations. It was not until the 1990s, however, that techniques weredeveloped for maintaining captive broodstock and breeding cod in captivity. Cod are generallyviewed as a possible direct substitute for salmon in existing net-pen operations because thegrow-out stage of cod production is almost identical to that of salmon. Some of the majormultinational companies shown in Figure 1, particularly Nutreco, are taking a lead in developingthis industry. A few technical hurdles exist, such as finding a suitable nutrition regime for larvae(unlike salmon, cod larvae have no yolk sac for nutrition and require zooplankton, brine shrimp,or other live organisms for feed) and establishing a sufficient number of juveniles to makeyear-round production possible because the natural spawning cycle of cod is short. Commercialcultivation of Atlantic cod is currently established in Norway, the United Kingdom, Canada, andIceland with production at about 1500 tons in 2002 . Norway is positioned to lead the global codaquaculture industry, just as it has done with salmon, and some sources predict that Norwegianproduction could reach 30,000 tons a year by 2008 . Canada and Scotland are following its lead.At this stage in the development process, commercialization of farmed cod depends on lowcapture rates of wild cod and high prices to remain economically viable.

蓝鳍金枪鱼是另一种肉食性物种,作为主要水产养殖产品上线,以应对野生渔业资源的严重下降和巨大的潜在利润率。与鳕鱼和大比目鱼不同,大多数养殖的蓝鳍金枪鱼都是放牧的,这意味着幼年金枪鱼在海上捕获,然后在网箱中养肥,直到它们达到上市规格。这个过程可能需要两个月到两年的时间,具体取决于捕获的幼鱼的大小。在给定的养殖场,多达2000条蓝鳍金枪鱼可能被限制在离岸的一个网栏中,通常有八个或更多的网栏组合在一起。澳大利亚自1990年代初开始养殖南部蓝鳍金枪鱼,取得了巨大的经济成功;1992年至2002年间,该行业的价值和数量分别以惊人的每年40%和16%的速度增长。大西洋和太平洋蓝鳍金枪鱼养殖场最近出现在地中海国家,如西班牙和克罗地亚,以及墨西哥,包括美国在内的其他几个国家也开始发展。在所有情况下,市场潜力都非常巨大,日本消费了大部分产出。所有地区都存在金枪鱼捕捞配额,限制了行业增长;然而,这些配额在澳大利亚以外的地区往往监管不力。出于商业目的圈养金枪鱼可能对该行业和野生种群的可持续性至关重要。自20世纪70年代以来就一直在尝试这样做,日本最近的工作通过人工饲养的蓝鳍金枪鱼产卵成功地结束了生产周期。

Bluefin tuna is another carnivorous species coming on line as a major aquaculture product inresponse to serious declines in wild fisheries stocks and large potential profit margins. Unlike codand halibut, most farmed bluefin tuna are ranched, meaning juvenile tuna are captured at seaand then fattened in cages until they reach marketable size. This process can take from twomonths to two years depending on the size of juveniles captured. On a given farm site, up to2000 bluefin tuna may be confined in a single net pen offshore, with eight or more net penstypically grouped together. Australia has ranched southern bluefin tuna since the early 1990swith great economic success; the value and volume of its industry grew by an astonishing 40%and 16% per annum, respectively, between 1992 and 2002. Atlantic and Pacific bluefin tunaranching has emerged more recently in Mediterranean countries, such as Spain and Croatia, aswell as in Mexico, and development is beginning in several other countries including the UnitdStates. In all cases, the market potential is exceptional, with Japan consuming most of the output.Tuna capture quotas exist in all regions and act as a constraint on industry growth; however,these quotas tend to be poorly regulated in regions outside of Australia. Breeding tuna icaptivity for commercial purposes will likely be critical to the sustainability of both the industryand wild stocks. Attempts to do so have been ongoing since the 1970s , and recent work in Japanhas succeeded in closing the production cycle by getting artificially reared bluefin to produceeggs.

海水养殖的未来愿景:

鉴于目前鱼类生产的趋势,海洋资源正处于危险之中。许多捕捞渔业正在衰退,海水鱼类养殖——通常被认为是解决过度捕捞和其他人类对海洋环境造成的压力问题的方法——给野生鱼类带来了额外的风险。海洋有鳍鱼水产养殖严重依赖野生捕捞来获取鱼粉和鱼油;它通过营养物质、有时是化学物质和药物排放物污染海水;它还可能通过疾病和寄生虫传播以及养殖鱼类从网栏逃逸到野外而威胁到本地鱼类种群。与此同时,水产养殖基本上是从海洋中生产更多鱼类的唯一途径,该行业似乎对减少海洋压力的新技术和管理实践反应迅速。当前有鳍鱼新品种的多样化进程以及将作业转移到开阔海域的前景为重新思考目前的有鳍鱼类养殖方法提供了一个合适的时机。

随着海洋有鳍鱼水产养殖业因市场机遇、科技进步和公共部门的鼓励而发展,需要将基于生态系统的管理方法与健全的商业方法结合起来。从长远来看,没有生态管理原则的私营部门海水养殖商业方法是不可持续的。同样,在没有适当关注商业激励措施的情况下实施基于生态系统的管理方法是不可行的。政府在整合商业和生态系统理念方面可以发挥重要作用,以免它们面临野生渔业和海水养殖业的崩溃,以及对海洋生态系统的进一步破坏。同时,建立普遍的、可认证的海水鱼类养殖最佳实践符合水产养殖业和保护社区的长期利益。

三个关键步骤可以帮助促进海洋有鳍鱼水产养殖的可持续性:识别具有强大市场潜力和适合养殖的低营养级海洋有鳍鱼,继续转向以植物为基础的饲料,以及在远离野生鱼类生活环境的环境中养殖鱼类(例如,通过更广泛地使用陆基水箱或封闭式袋网围栏)。此外,促进综合水产养殖,其中贻贝、海藻和其他物种在有鳍鱼类附近养殖,以回收废物,这有助于减少营养物污染。目前存在几个生态综合海水养殖系统,但此类系统的商业可行性取决于更大规模的实验和对联合培养物种之间相互作用和过程的进一步研究。

A FUTURE VISION FOR MARINE AQUACULTURE

Ocean resources are in jeopardy given current trends in fish production. Many capturefisheries are in decline, and marine finfish aquaculture—often considered to be the solution toproblems of overfishing and other human stresses on the marine environment—poses additionalrisks to wild fish stocks. Marine finfish aquaculture is heavily dependent on wild capture for fishmeal and fish oil inputs; it pollutes marine waters through nutrient, and sometimes chemical andpharmaceutical discharges; and it potentially threatens native fish populations via disease andparasite transmission and the escape of farmed fish from net pens into the wild. At the sametime, aquaculture is essentially the only avenue to produce more fish from the oceans, and theindustry appears to be responsive to new technologies and management practices that reducestress on the oceans. The current process of diversification into new finfish species and theprospect of moving operations into the open ocean provide an opportune time to rethink thepresent approach toward marine finfish aquaculture.

As marine finfish aquaculture grows in response to market opportunities, improved scienceand technology, and public sector encouragement, there is a need to marry an ecosystem-basedmanagement approach with a sound business approach. A private-sector business approach tomarine aquaculture without ecological management principles is not sustainable in the long run.Likewise, an ecosystem-based management approach implemented without proper attention tobusiness incentives is not feasible. Governments have an important role to play in integratingbusiness and ecosystem ideals, lest they face collapse both in wild fisheries and marineaquaculture, as well as further damage to marine ecosystems. At the same time, an internationalagreement among aquaculture-producing countries could help to “level the playing field” andpromote environmentally sound practices. Establishment of universal, certifiable best practicesfor marine finfish farming is in the long-term interest of both the aquaculture industry and theconservation community.

Three key steps could help promote sustainability of marine finfish aquaculture: theidentification of lower trophic level marine finfish with strong market potential and suitability forfarming, the continued move toward vegetable-based feeds, and farming fish apart from theenvironment where their wild counterparts live (e.g., through more widespread use ofland-based tanks or enclosed bag net pens). In addition, promoting integrated aquaculture, inwhich mussels, seaweeds, and other species are grown in close proximity with finfish for wasterecycling, could help to reduce nutrient pollution. Several ecologically integrated marineaquaculture systems currently exist, but the commercial viability of such systems depends onlarger scale experimentation and further investigation of the interactions and processes amongjointly cultured species.Naylor R, Burke M. Aquaculture and ocean resources: raising tigers of the sea[J]. Annu. Rev.Environ. Resour., 2005, 30: 185-218.